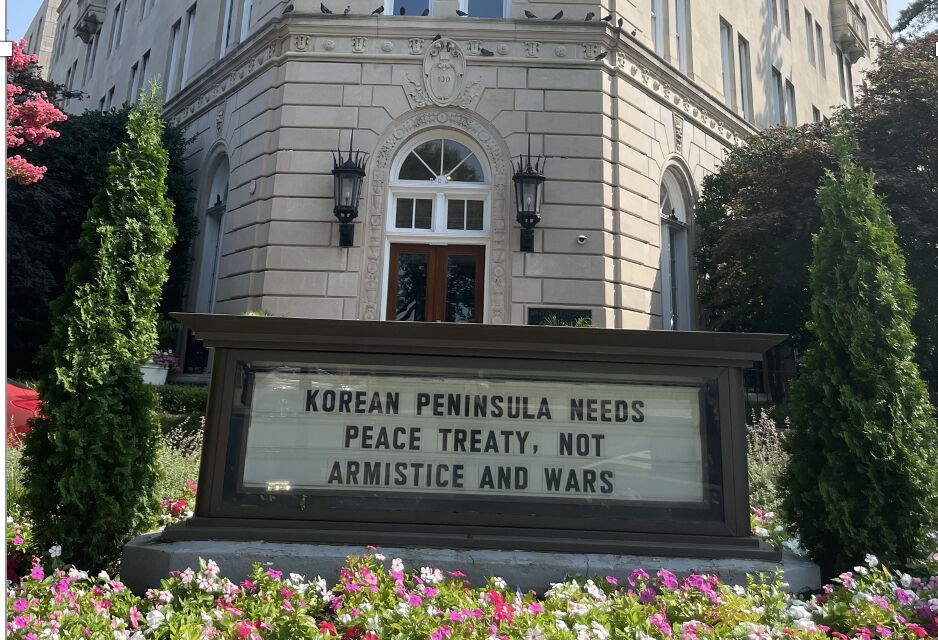

The Korean Peninsula Needs Peace Treaty, Not Armistice and More Wars

Marking the armistice agreement that put the Korean War in ceasefire mode 70 years ago this week, The Rev. Dr. Liberato (Levi) Bautista offers his reflection for peaceful coexistence in the Korean Peninsula, Asia Pacific region, and the world.

After 70 years of armistice, the message from the Korea Peace Appeal is clear. There should be no more wars on the Korean Peninsula – and we must pray for God’s peace in this peninsula and for the world. The ecumenical movement worldwide, including United Methodists, is equally precise and supportive of this message.

We have witnessed since the breakdown of the Hanoi summit in February 2019, peace talks between the U.S. and North Korea remain at a stalemate. One year later, the Covid-19 pandemic closed the borders between the peninsula’s North and South indefinitely.

But in all these circumstances—political and otherwise—the longing desire for just and lasting peace in the Korean Peninsula remains strong. The ecumenical movement in the Korean Peninsula and worldwide through the World Council of Churches continues to resource this longing desire for peace.

Martin Luther King, Jr. once said, “Those who love peace must learn to organize as effectively as those who love war.” Organizing peace is indeed our primordial task, if not a burden.

But alas, today, wars appear far more straightforward, and their funding far more profuse and available than any project pursuing peace. For those who love peace and struggle for peace, such a predisposition to war is daunting.

In the end, sanctions are a distraction from just and lasting peace.

The agenda for war speaks of arsenals of death-dealing instruments. In contrast, sanctions seem to always be the one tool for peace. However, for decades, sanctions have served to “ensure that the anti-war and peace movement cannot find its bearings and gather strength.”

Peace activists must organize harder and more systematically if peaceful coexistence in a multipolar world is to be achieved. Organizing provides the venue for multilateral cooperation so that no singular power dictates the governance algorithm for peace.

The hardware of war and the hard-wired decision-making for militaristic dominance demonstrate that the classic assumption remains true: war makes money and fuels the economy.

The task of peacebuilding is even more complicated because the argument is between the hardware of war and the software of peace. The instruments of war are injurious and lethal, yet the implements of peace often appear safe for these deadly instruments.

Diplomacy and engagement must form part of a peace tool kit.

The right to peace is a fundamental human right. The UN Declaration on the Right of Peoples to Peace (1984) puts war squarely at odds not just with peace but with human rights: “Life without war is the primary prerequisite for the material well-being, development and progress of countries, and for the full implementation of fundamental freedoms.”

I worry about an unnuanced use of the phrase “alternatives to war.” From my faith perspective, Christian and United Methodist, peace cannot be the alternative; peace must be imperative in the Korean Peninsula and everywhere. Christ is our peace, and that’s a declarative statement rather than an option.

Why do I say this? This alternative posture partly makes the notion of the so-called “culture of peace” again consigned to the software of peace, compared to the hardware of war.

No matter the progressive backing for constructing the theory and practice of a culture of peace, my concern has yet to be in the realm of culture. My fears lie in politics and economics being relegated to war. And peace relegated to culture.

Even as we perfect the theory and practice of a culture of peace, the war-mongers and militarists are controlling the political levers of decision-making and the economic purse strings of financing war and defunding peace.

Today, the UN, the primordial instrument of multilateral action, indeed of collective decision-making among nation-states, is challenged by unilateralism, xenophobic nationalism, and exclusionary politics that has pitted peoples of the world against one another, thereby fostering a climate of fear and violence that has fed anti-immigrant sentiments, even acts of fragmentation, extremism and terror.

Koreans longing for peace on the Korean Peninsula declare their desire to “resolve the conflict with dialogue and cooperation instead of sanctions and pressure” and that we should “break from the vicious cycle of the arms race and invest in human security and environmental sustainability.”

But the voice for peace must be louder and organized, mainly because we are increasingly seeing the curtailing of democratic discourse in a public square that is shrinking, all to the detriment of a collective undertaking to imagine lasting ways and means for peace and genuinely putting to end lingering conflicts and avoiding the start of yet other wars.

The Rev. Dr. Liberato Bautista is Assistant General Secretary for United Nations and International Affairs of the General Board of Church and Society of The United Methodist Church and serves as the Non-government Organization’s (NGO) Main Representative to the United Nations worldwide. Rev. Bautista has traveled extensively in the Korean Peninsula for the last four decades.