United Methodists Support Investigation of Abuses in the Philippines

Church leaders, groups under attack for advocating for poor and Indigenous communities

United Methodists are adding their voices to a renewed call for an independent investigation by the United Nations and international community of human rights violations in the Philippines.

Three reports by INVESTIGATE PH undergird the United Methodist support and longstanding commitments to the Filipino people and Indigenous communities in the Philippines, said the Rev. Dr. Susan Henry-Crowe, general secretary of the General Board of Church and Society of The United Methodist Church.

The National Association of Filipino American United Methodists (NAFAUM) — representing Filipino congregations and ministries throughout the U.S. and Canada — also has endorsed the work of INVESTIGATE PH.

Henry-Crowe was one of 10 commissioners for INVESTIGATE PH who took part in four online hearings in July and August of 2021. She said she heard dozens of disturbing stories from religious leaders, educators, lawyers and young people about the actions of the government led by Philippine President Rodrigo Duterte.

Churches and religious groups who advocate for the poor and Indigenous peoples are among those who have been directly attacked, Henry-Crowe said. The Indigenous groups being persecuted include the Lumads, some of whom are United Methodist.

From southern Philippines, the Lumads have been caught in the middle of combat between government soldiers and armed rebels. In the fall of 2020, for example, 26 Lumad families who were members of Beho Omor United Methodist Church, were among 58 families forced to flee their homes and seek shelter at an evacuation site because of the fighting.

The Philippine government has closed some 215 Lumad schools, affecting the education of 10,000 students, Henry-Crowe said.

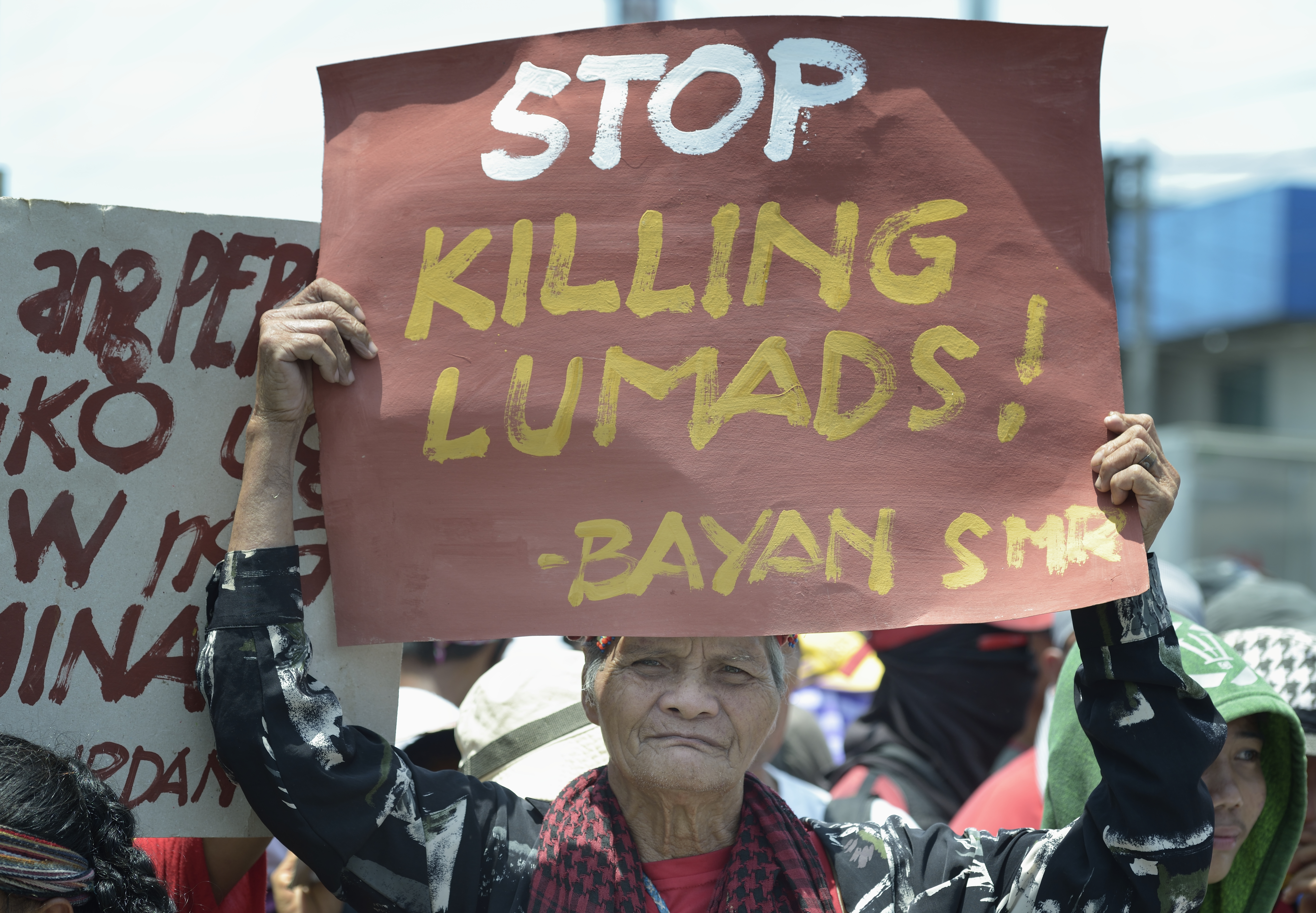

An Indigenous man holds a sign during a demonstration in 2016 outside a military base in Davao, on the southern Philippine island of Mindanao. Hundreds of Indigenous (known locally as Lumads) were living in a church compound in the city, chased out of their rural villages by paramilitary squads. Photo © Paul Jeffrey, Life on Earth Pictures

“President Duterte’s ‘whole of nation’ strategy against critics — in the name of stopping communist armed conflict — has involved attacks on the education system and teachers, which is evident in the ongoing closure of Lumad schools, including occupation of schools, arrest of children and attacks on teachers and universities by state authorities,” she said.

The government also has employed “red-tagging” as part of the tactics used against those who oppose its policies.

“Red-tagging is labeling people who the government does not agree with as a threat to society, using it as a rationale to violate their civil and human rights,” Henry-Crowe explained. “Church leaders and groups in the Philippines are among those who have been red-tagged.”

The National Council of Churches in the Philippines, in which United Methodists play an active role, partnered with Rise Up for Life and for Rights in an Oct. 7 online oral statement to the U.N. Human Rights Council. The statement was presented through the World Council of Churches during the regular debate segment of the ongoing 48th regular session of the Human Rights Council.

Rise Up disputed Duterte’s claims to the U.N. about his government’s accountability on the issue of civil rights and echoed the call that the Council conduct “an independent investigation into the widespread and systematic killings and other human rights violations in the Philippines.”

A new report by Michelle Bachelet, U.N. High Commissioner for Human Rights, to the Council pointed to continuing human rights violations and the absence of accountability for those violations and the killings of the Filipino people, Bachelet said she also is “deeply concerned” about the continuing reports of red-tagging.

A Filipino journalist, Maria Ressa, recently received international recognition for her reporting on corruption and human rights abuses in the Philippines when she and a Russian journalist, Dimitri A. Muratov, were awarded the 2021 Nobel Peace Prize.

The 18th woman to receive that award, Ressa told the New York Times that by selecting two journalists, the Nobel Committee showed the world the dangers of being a journalist today. The Philippine government had filed 10 arrest warrants against her, she said, with seven legal cases still pending.

The INVESTIGATE PH final report declared that the suffering of people in the Philippines under the policies of President Duterte, who took office in July 2016, are worse than that of the Marcos dictatorship “Landlessness, unemployment and poverty have widened, and extrajudicial killings of civilians by state forces in these five-and-a-half years have long surpassed those during the sixteen years of the notorious Marcos dictatorship,” the report’s conclusion said. “Women, children and Indigenous people have especially suffered. People’s collective rights to self-determination, development and peace are grievously violated.”

Human rights violations have been an ongoing issue in the Philippines. In its 2016 Book of Resolutions, General Conference — the top legislative body of The United Methodist Church — spoke out against previous Philippine governments that allowed extra-judicial killings, enforced disappearances and other types of human rights violations to be “conducted with impunity as the perpetrators remain free and exempted from justice while the victims are vilified and dismissed as subversives and undeserving of any form of justice… (Resolution 6117).”

Resolution 6118 also raised the concern over militarization in the Philippines and found “very alarming” the “increasingly militarized approach of both the Philippine and U.S. governments to the economic development of and humanitarian crises in the Philippines.”

The United Methodist Church has long supported the right of self-determination for national minorities in the Philippines and has called for formal peace talks to unite the country “through a broad alliance of patriotic and progressive forces and a clean and honest coalition government for genuine national independence and democracy against any foreign domination or control and against subservience (Resolution 6138).”

NAFAUM has condemned “the severe escalation of human rights abuses” and under the Duterte government and expressed concern for United Methodist bishops and leaders in the Philippines being targeted “for their social justice stances and acts in the name of Christ’s Gospel for the poor and the marginalized.”

The association is coordinating with the General Board of Church Society and other groups to strengthen the denomination’s human rights advocacy and solidarity work in the Philippines.

It is important to continue to speak out against the current human rights violations in the Philippines, Henry-Crowe said.

“The prophetic voice of the church is intrinsic to its work as a faith body,” she noted. “We claim this work in the public sphere with autonomy, knowing that in the Philippines as in the U.S, freedom of religion and belief are protected human rights.”

Bloom is the interim communications director for the General Board of Church and Society.