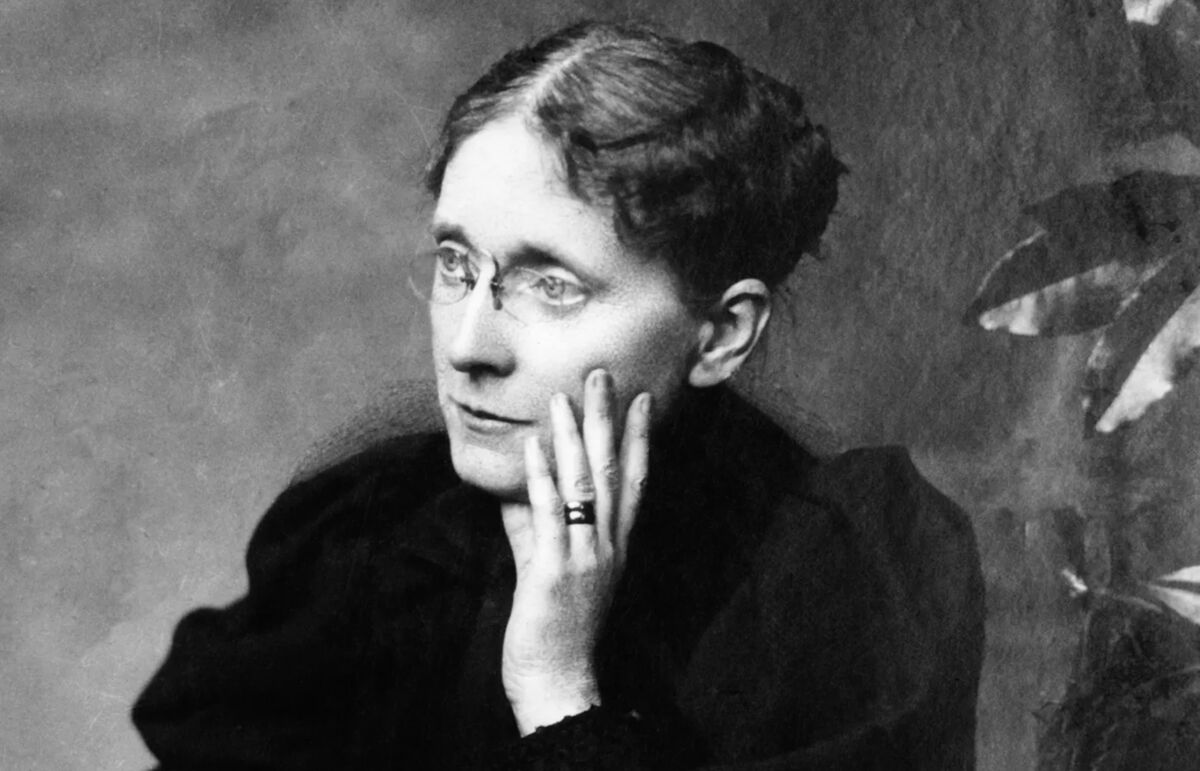

Celebrating Women's History Month Highlighting Methodist Frances Willard

She was known for her work with the temperance movement as president of the Woman's Christian Temperance Board, but her impact was empowering women's voices in the pulpit and at the ballot box.

By Dr. Ashley Boggan D., general secretary, The UMC’s General Commission on Archives and History

To celebrate women’s history month and the 100th anniversary of the UM Building, I want to highlight one of my favorite Methodist “sheroes,” Frances Willard. Before diving into her contributions, it does need to be noted that Frances Willard was not immune to the racism of her time. Her advocacy was largely limited to white women and she was famously (and rightfully) critiqued by journalist Ida B. Wells for her segregation of the Woman’s Christian Temperance Union (WCTU).

Frances was born in 1839 and is most known for her work with the temperance movement as president of the WCTU. Frances was a political genius of her day. She was raised in a Methodist family in the New York but relocated to Evanston, Ill., to focus on women’s education. She taught for 10 years and then served as president of Evanston College for Ladies in 1871. Seeking to normalize co-education, she treated her female students no differently than the male students of Northwestern.

Quick to ensure women were taught subjects like science, literature, and the arts, her approach challenged traditional gender roles and expectations for women’s education at the time. She encouraged them to think critically, pursue intellectual interests, and develop a sense of social responsibility. Many of her students went on to become leaders in various fields, and some joined her in social reform efforts later in life. Her educational career ended after reaching its peak. Evanston College for Ladies merged with Northwestern in 1874 and Frances became the first female dean of the women’s division of a coeducational college.

After teaching, she joined the temperance movement which was gaining popularity in the mid-1870s due to a new woman’s organizations that was making its way across the nation. The Woman’s Christian Temperance Union brought women of all ilk together to reform the nation through the regulation of liquor. By 1874, Willard was serving as the president of the Chicago chapter of the WCTU. At the first national convention of the WCTU, she was elected its corresponding secretary; in other words, she was in charge of promotion and membership training of the organization. Within five years, she was named its president, a role she would hold until her death in 1898.

Willard was quite active within the Methodist Episcopal Church in the Chicago area, where she encouraged women’s participation and ordination. In May 1880, she attempted to address the General Conference of the MEC in order to bring greetings as the president of the WCTU. However, women were not allowed to address the General Conference, and her request caused an uproarious debate on the “woman question.” This debate led Willard to coordinate educational efforts throughout the denomination on women’s religious authority. She wrote “Woman in the Pulpit,” which unapologetically argued that women had an equal standing with men and should be allowed not only voice in the denomination but full ordination rights.

In 1887 she was elected as a lay delegate to the 1888 General Conference by the Rock River annual conference, one of five women elected that year. Upon arrival, the male delegates refused to allow the women to enter the “bar” and be seated as delegates. Willard and her fellow advocates did not shy away in defeat, but again turned to education and advocacy. Between the 1888 and 1892 General Conferences, they used their national newspaper to advise women on how to speak with their local ministers about allowing women to enter the General Conference. They supplied them with copies of “Woman in the Pulpit” as a means to educate themselves and to give to their clergy. Their efforts continued to falter but started conversations that eventually led to women being seated as delegates in 1904.

She pushed Methodist white women towards a new concept of religion. For her, one’s Methodist faith should compel you to make yourself uncomfortable, to push your own boundaries, in order to spread the love of God to as many people as possible. During Willard’s era, for Methodist women, this meant speaking up and acting out. Women during Willard’s time were expected to be pious, pure, and submissive. The genius of Willard was that she took these three “ideals” and used them to agree for reasons why women needed to step out of the home. If women were truly pious then they could not sit in their homes and watch poverty, oppression, and corruption run rampant.

Their faith should compel them to act in order to better the world around them – to make the world more Christ-like. She used a rather “conservative” understanding of womanhood, particularly of Christian womanhood, to compel women to act beyond the norms of their gender. She brought women together and taught them how to be socially active. Under her leadership the WCTU became the largest women’s organization in the US.

For Willard, the social sin was alcohol consumption, but the systemic sin was the lack of women’s voices both in the pulpit and at the ballot box. Teaching women how to be brave enough to take small steps towards radical change at the local level was pivotal in seeing the implementation of various rights, including the right to vote.

Willard’s process allowed women to see that they could make a difference outside of their homes. It taught them how to use their voices outside of the home for social change. It gave them a small taste of social authority. In sum, for Willard “God is action – let us be like God.”

Dr. Ashley Boggan D. is the General Secretary of the General Commission on Archives and History. She earned her PhD from Drew Theological School’s Graduate Division of Religion and an M.A. in American Religious History from the University of Chicago’s Divinity School. She is the author of “Nevertheless: American Methodists and Women’s Rights” (2020); “Entangled: A History of American Methodism, Politics, and Sexuality” (2018); and added to the revised “American Methodism: A Compact History” (2022).