Lawson to receive Congressional Gold Medal

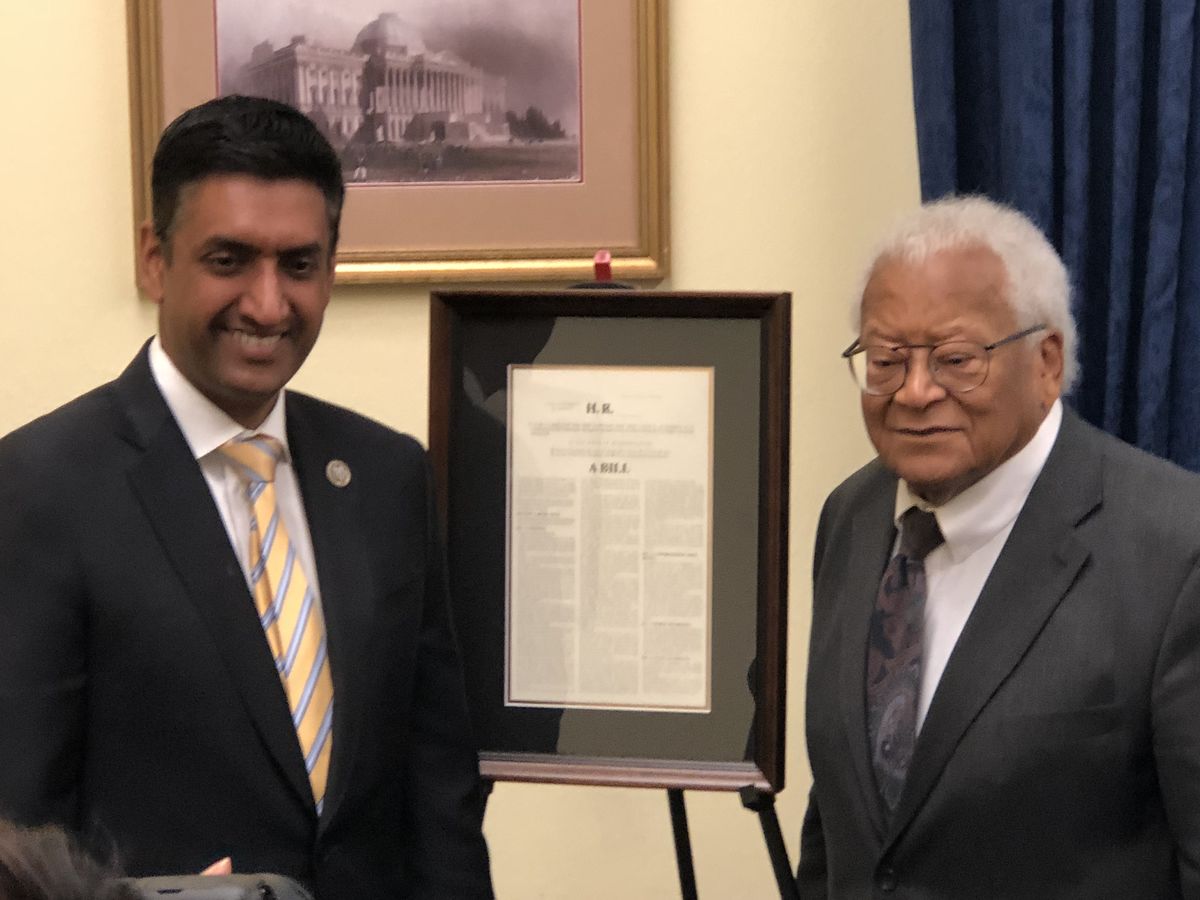

U.S. Rep. Ro Khanna, along with several members of Congress, have nominated United Methodist pastor and leader of the Civil Rights Movement, the Rev. James Lawson, to receive the Congressional Gold Medal, one of the nation's highest honors.

In the course of his life as an activist, the Rev. James Lawson has endured racial epithets, accusations of anarchy, threats of physical violence, expulsion from a leading university, overnight lock-ups and months in prison.

Now, the government which often opposed Lawson’s work for civil and human rights in decades past is poised to award him one of the nation’s highest honors: The Congressional Gold Medal. The resolution, co-sponsored by a group of representatives including fellow Civil Rights icon John Lewis, was introduced in the House of Representatives Wednesday, Nov. 14.

For the 90-year-old Lawson, a United Methodist minister whom Lewis has called “the architect of the Civil Rights movement,” the recognition is “humbling,” but also an affirmation that his work for nonviolent social change has not been in vain. “It makes me aware that what I was given in my call by God, even before I knew what it was, has borne some good fruit,” Lawson reflects. “But the work of translating the Gospel in terms of nonviolence is not over. I still have a calling for that work, and I still have a responsibility to God to do it.”

Lawson’s illustrious career as a fighter for freedom and justice in the name of the Gospel stretches back nearly seven decades. As a college student in Ohio in the late 1940s, he joined the Fellowship of Reconciliation, the nation’s oldest peace organization, and the allied Congress of Racial Equality, where he first encountered Mohandas Gandhi’s philosophy of nonviolence.

After reading Gandhi’s autobiography in 1947, Lawson says he declared himself “a practitioner of nonviolence and a follower of Jesus.”

He credits his mother and his early experiences in the Methodist church with laying the foundation for a lifetime’s commitment to nonviolence. “My mother preached and taught God’s love, and said that fighting, the use of anger, even among children, was unacceptable,” Lawson recalls.

The first big test of his commitment to nonviolence came in 1949, when Lawson received a draft notice months before the onset of the Korean War.

“The [Selective Service] law was similar to Jim Crow, and applied unfairly, so I sent my draft cards back,” Lawson recounts.

As a student and prospective minister, he could have requested a deferment, but for Lawson, refusing to exempt himself from a draft that unfairly targeted minorities and those who could not afford an education (as he could) was “an act of conscience” and “an attempt to pursue Jesus.” As a result, Lawson was convicted of draft evasion and sentenced to two years in prison, of which he served 13 months.

While in prison, Lawson wrote that he was “an extreme radical, which means the potent possibility of future jails. My life will be rather exciting, and [will] offer security only in the sense of service to God’s Kingdom.”

Lawson’s prediction was prescient. Shortly after he was paroled in 1952, the Women’s Division of the Methodist Board of Mission offered the now-licensed minister a position as a missionary to India. Among other things, it meant that he could follow in the footsteps of Gandhi and engage with people who had been directly involved in India’s nonviolent independence movement.

During his three years there, Lawson met with Indian Prime Minister Jawaharlal Nehru and other close associates of Gandhi, and most importantly, deepened his study of satyagraha, Gandhi’s philosophy of nonviolent resistance. He also discovered important points of connection between the teachings of Jesus and the philosophy of Gandhi.

“Gandhi’s political and social ideas coincide with the teachings of Jesus in the Bible,” Lawson reflects. “Gandhi was aware of that. The scriptures are firm that you cannot overcome evil with evil, but that evil has to be resisted by good. … That of course is one of the overarching laws of nonviolence and of life. Responding to evil with your own form of evil just escalates and increases the evil. Gandhi knew that, and Jesus taught it.”

Lawson says that Gandhi started reading the Bible in his early years in South Africa and later adopted Jesus’ Sermon on the Mount as a kind of model teaching, to be regularly read aloud in his presence. In fact, Gandhi’s definition of nonviolence as “love in action” seems very close to Jesus’ teaching in Matthew 5-7; Lawson is credited with being a major force for the spread of Gandhi’s philosophy in the United States and for seeing parallels between India’s struggle for independence and African-Americans’ struggle against segregation.

It was while serving in India that Lawson excitedly read of a young Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. and the Montgomery Bus Boycott.

Not long after, Lawson returned to the United States to undertake graduate work at Oberlin College, where he met King, who was on a speaking tour. Impressed with Lawson’s knowledge of Gandhi, King urged the newly returned graduate student to come south and join the Freedom Movement.

The next year (1957), Lawson became only the second African-American to enroll at Vanderbilt Divinity School in Nashville, Tennessee, where he also took on the job of southern organizer for the Fellowship of Reconciliation. It was in the basement of a Methodist church in Nashville that Lawson led the first of numerous volunteer trainings in the Gandhian art of satyagraha.

In time, King would come to praise his friend and colleague as the “leading theorist and strategist of nonviolence in the world.”

Among the first of the Freedom Movement volunteers whom Lawson trained was a 19-year-old student from Fisk University named John Lewis. Lewis was among a group of young volunteers, including Diane Nash, James Bevel and Marion Barry, whom Lawson prepared in 1959 and 1960 to integrate downtown Nashville businesses using nonviolent direct action.

“It was at the ‘feet’ of Jim Lawson that I came to understand and accept the discipline and philosophy of nonviolence, not just as a tactic, but as a way of life,” Lewis recalled in an email. “[He] was very clear about the danger that we would face standing up to segregation and racial discrimination in Nashville. His teaching prepared us to bear the indignities of abuse in service to a cause greater than ourselves. He taught us to see these actions in a philosophical light and not to take them personally. He also told us we might be beaten, arrested, and taken to jail, something my mother had warned me never to do.”

Many of the young protesters did go to jail, but within a few months, Nashville became the first major city in the South to desegregate public facilities. The Nashville lunch counter sit-ins, which Lawson helped orchestrate, became a model for successful nonviolent direct action throughout the Civil Rights Movement.

Ironically, Lawson’s involvement with the sit-ins, and their success, led to his ouster from Vanderbilt University. Segregationists pressured university officials to expel the rights activist; the dean of the Divinity School and a number of its professors resigned as a result. But in 2006, after decades of apologies, Vanderbilt invited Lawson back as a visiting professor, 46 years after he was unceremoniously sent away.

The same year as his expulsion (1960), Lawson was invited to give the keynote address at the founding of the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee, which Lewis would later chair. Lawson wrote the student-led rights organization’s original Statement of Purpose, beginning, “We affirm the philosophical or religious ideal of nonviolence as the foundation of our purpose, the presupposition of our belief, and the manner of our action.”

The congressional resolution, introduced by U.S. Rep. Ro Khanna of California, notes, Lawson and his group of activists were instrumental in many of the Civil Rights campaigns that followed, including the Freedom Rides, Freedom Schools, the 1963 March on Washington and the Mississippi Freedom Summer, to name only a few.

In the case of the 1961 Freedom Rides, Lawson rode from Montgomery, Alabama, to Jackson, Mississippi, with a group of his trained volunteers and went to jail with them when they were arrested for breaking interstate bus segregation laws. But they met with U.S. Attorney General Robert Kennedy and eventually won their suit to desegregate interstate travel.

In 1962, Lawson moved to Memphis, Tennessee, to become pastor of Centenary Methodist Church, although he continued to lead regular trainings in nonviolent direct action in Montgomery and other cities.

It was in Memphis in 1968 that Lawson became involved in the cause of the city’s Black sanitation workers, chairing the strike committee that supported their demands for a living wage, safer work conditions and equal treatment with their white colleagues. And it was in support of their cause that Lawson invited his friend King to Memphis that fateful spring to bring a national spotlight to the workers’ plight.

Although King was lost on the balcony of the Lorraine Motel, the campaign went on, becoming “the first successful effort to organize African-American municipal workers in the South,” according to the proposed House resolution. Lawson was an instrumental part of that.

Lawson left the South in 1974 to become pastor of Holman United Methodist Church in Los Angeles, California, where he continued his advocacy for racial and social justice and the promotion of nonviolent direct action.

In the decades since, and as pastor emeritus, he has worked with the labor movement and the American Civil Liberties Union, protested U.S. support for El Salvador’s former military regime, chaired the Clergy and Laity United for Economic Justice group, helped found an Immigrant Workers Freedom Ride and the post-9/11 Interfaith Communities United for Justice and Peace organization, and taught nonviolence at Vanderbilt, the California state university system, and at Harvard University.

While the congressional gold medal resolution is keyed to Lawson’s 90th birthday, this past September, sponsor Khanna says the recognition of Lawson’s work is a timely reminder of the sacrifices Americans and people around the world have made for the cause of freedom.

“At a time of darkness, when it seems that we are actually moving backwards in the struggle for justice and freedom in our own country, we should look to figures like James Lawson, Gandhi, King and John Lewis [for inspiration] and be more resolved to stand up for our values,” Khanna asserts. “He [Lawson] appeals to a different dimension of America and of humanity. … No leader has imagined a more noble form of politics for the human soul than James Lawson. He stands at the intersection of Gandhi and King, speaking to what politics should be at its most noble.”

For his part, Lewis suggests that “the philosophy and discipline” of nonviolence that Lawson has spent his life teaching and sharing “is needed in this country now more than ever before. … Reverend Lawson [can] offer the people of this nation an alternative lesson about the power of peace to transform America,” Lewis asserts. “His teaching [can] allow us to move away from the rancor of separation and division to understand that we are one people, one family — the human family.”

Like Lewis, Khanna has a personal investment in seeing Lawson receive this special recognition for his work. Khanna’s grandfather, Amarnath Vidyalankar, was a freedom fighter in Gandhi’s nonviolent independence movement who spent four years in jail for his part in the struggle to liberate India from British rule. “No one has done more to bring Gandhi’s principles to the United States than James Lawson,” Khanna declares. “He influenced Dr. King’s thinking about Gandhi, he influenced John Lewis, and many others. … Every American should grow up knowing his story.”

Khanna says that one of things the congressional resolution attempts to do is explain just how significant Lawson has been to civil rights movements in the United States and around the world, citing the anti-apartheid movement in South Africa led by Nelson Mandela. Khanna’s team has spent many hours with Lawson, collecting the details of his life in India, in the American Civil Rights Movement, as a minister and in other endeavors. Their work is intended to provide “a definitive account” of Lawson’s life that will contribute to Civil Rights history and be preserved in the congressional record.

For U.S. Rep. Emanuel Cleaver of Missouri, another of the bill’s co-sponsors, Lawson is “without a doubt, one of the top 10 most influential Black people of the 20th century.” Himself a United Methodist minister, Cleaver followed Lawson’s younger brother, the Rev. Phillip Lawson, as pastor of St. James United Methodist Church in Kansas City, Missouri, in the early 1970s. It was largely through Phillip Lawson and from his involvement in the Southern Christian Leadership Conference that Cleaver got to know James Lawson.

“I tell people [James Lawson is] probably more responsible for the things that went right in the SCLC and in the greater Movement overall because of his nonviolent influence,” Cleaver says. “His fingerprints are on every major Civil Rights victory because of how much he influenced the direction of the SCLC.”

Cleaver describes himself as being from a family of preachers on the one hand and members of the Black Panther Party on the other. (Two of his relations are former Panthers Eldridge Leroy Cleaver and Pete O’Neal, Jr., who remains in exile in Tanzania.) Cleaver says that at one point as a young man facing the realities of racism in America, he found himself at a crossroads. “Should I go off and be a Panther, or go the way of my other family members, a lot of them clergy?” he recalls. Cleaver chose “the church path” in large part because of the example and influence of minister-activists like Lawson.

Lawson is grateful for the influence that he has been able to bear over the years, but is quick to credit it to “the work of God” and not his own effort. In fact, he wishes that the “distinction” of how faith, the church and “the call of Jesus” provided a foundation for the Freedom Movements of the 1950s and ‘60s were better known.

Reflecting on these times, he says, “We have seen how history can be transformed through the Gospel of Jesus. It is a life force that can transform my life and my family’s lives and all of society. … With God’s help, we can reshape the earth so that, as Isaiah [65:23] says, ‘no one will labor in vain and no baby will be born into calamity.’ That’s not some pie in the sky vision. It’s possible, and it’s where God wants us to be.”

He then adds, as if in afterthought: “There is more to do.”

Editors note: The article has been updated to include the fact that it was the Women’s Division of the Methodist Board of Missions who engaged Lawson in his assignment to India.